Intestinal Stone (Enterliths) a colic risk

Enteroliths are large, hard as a rock, concretions of minerals which develop in the large intestine of a horse. They form when minerals come out of solution. The principal mineral is magnesium ammonium phosphate. The minerals congregate around some hard objet called the nidus. The nidus can be a nail, a pin, or a coin, but most commonly is a small stone.

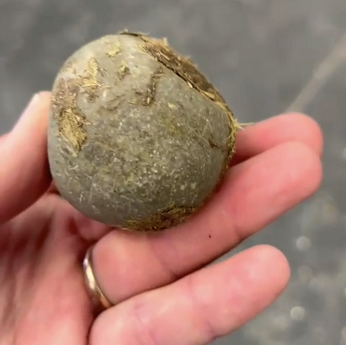

Here is a picture of a plum sized enterolith that was found in the manure of a horse.

They can become large enough, often about the size of a grapefruit, to obstruct the intestine and cause acute colic. I had one client’s horse who had an enterolith discovered during colic surgery the size a bowling ball.

The rate of growth of an enterolith is variable. In some horses an enterolith can grow to a size which causes obstruction within a year. Among breeds, Arabians and Morgans appear to have the highest risk.

It is true that some horses will not form enteroliths and others will under any conditions. Diet has frequently been suggested as a contributing factor. In the 1800’s it was concluded that large concentration of nitrogen, magnesium, and phosphorous in the diet was associated with an increase incidence of enteroliths. Wheat bran contains significant amounts of these elements. When wheat bran was removed from the diet, the incidence of enteroliths decreased. Alfalfa has also been suggested as a factor. Alfalfa is high in nitrogen and in some areas it is likely to be relatively high in magnesium.

The most important factor may be the diet’s ability to raise the pH. PH is a measure of the acidity of an environment. A lower pH is more acidic. A higher pH is more basic. It has been suggested that when the intestinal pH is 6.5 or below (on a 14 point range) the incidence of enteroliths is decreased. Alfalfa is known to slightly raise the pH of the rumen (the cow’s largest stomach), it may be doing the same in the intestine of horses encouraging minerals to come out of solution.

Enteroliths are important because they can obstruct the large intestine of horse leading to colic. The most common scenario associated with an enterolith caused colic is that of an older horse with a number of low grade episodes of colic which may increase in severity. The obstruction may only be partial allowing the horse to pass small amounts of manure and mineral oil if that has been given as part of treatment for an episode of colic. While this is a classic history, enteroliths can form in horses of almost any age. Enterolith caused colic episodes are frequently low grade to start. However, in a case where a complete obstruction has occurred, severe pain can result suggesting a more acute cause of colic.

Diagnosis with out surgery is difficult. X-rays have been used to diagnosis horses with enteroliths and do find the majority of enteroliths if present. However, this approach has limitations. In larger adult horses the size of the abdomen may make x-rays unusable. In others, an enterolith may show up if it is in an area just behind and below the diaphragm but not if it is farther deep in the abdomen. So, x-rays finding are definitive when they show up an enterolith and not when they do not. You could have a false negative screening. In rare cases the stone may be felt on rectal palpation and an occasional horse may even pass a small enterolith out with it’s manure as pictured above. For the most part, the diagnosis is only made when a colicky horse is taken to surgery.

Prevention and treatment of enteroliths focuses on changing the diet. Anecdotal reports suggest that feeding 8 oz. of apple cider vinegar two times per day has reduced the incidence of enteroliths. Again this may be related to lowering the pH (making the colon contents more acidic). In a study of ponies fed apple cider vinegar the pH dropped from 6.5 to 6.0 after about 21 days. It appeared safe to feed for as long as 90 days. Lowering the pH further can cause it’s own set of problems. So, current recommendations in horses which are at risk is to feed vinegar on a 6 weeks on, followed by 6 weeks off regimen. Other recommendations include switching from alfalfa to grass hay if that is the currently given to an affected horse or horses at an affected farm, and increasing the ratio of feed that is being given as grain while eliminating the feeding of bran. Grain has a slightly acidifying property.

Most horse owners are aware of enteroliths. It can be difficult to put in perspective the risk of any one horse coming down with the problem. In no area is the condition common. The problem occurs throughout the country. There is a higher incidence in the Southeast United States and in California than in other parts of the country. UC Davis reported an incidence of 42.2 cases of enteroliths per 10,000 patients. Since most horses never become patients at UC Davis, the likelihood of any one horse developing an enterolith is very small. In my own experience in the last 10 years, I treated only 2 colic cases that turned out to be enteroliths and 1 addition case where a horse passed an enterolith in her manure but was otherwise fine.

On a very few occasions owners have called me having found an enterolith being passed in a horse's manure. In such a case, there is value in taking radiographs (x-rays). This has to be done at a referral facility with a more powerful x-rays machine capable of penetrating a horse abdomen. While not perfect test, because it can miss some enteroliths, if they are there, radiographs can find them in the majority of cases and give you an assessment of how large they are. If the enteroliths found are small, then we usually do the preventative measures mentioned earlier and consider recheck radiographs every 6-12 months to make sure that they aren't growing larger. If the enteroliths are of a size that could cause an obstruction, some owners will do elective abdominal surgery to remove them. This can be done either at the time the enteroliths are found or when it is more convenient for them, for example, if they want to finish a show season. It involves a 3 or 4 month recovery period following the surgery. Certainly, there is not a requirement to do surgery remove an asymptomatic enterolith. However, knowing that one is there and has the potential to cause a problem is enough for some owners to want to be proceed.

Here is the x-ray from the horse that passed the plumb sized enterolith pictured above.

In this case the owner elected to do preventative colic surgery and remove the stones. Here is a picture of the stones that were removed. Three are the size of a baseball.

Fortunately, this horse recovered and is back training and competing.